D-Day Remembered

So where will you be on the 6-7th of June? TheEye will be in Normandy where 65 years ago to the day his uncle waded ashore on D-Day. Unlike the chaps whom George had only known for a short while (but it felt like a lifetime) he managed to make it up the beach and become not-dead.

So where will you be on the 6-7th of June? TheEye will be in Normandy where 65 years ago to the day his uncle waded ashore on D-Day. Unlike the chaps whom George had only known for a short while (but it felt like a lifetime) he managed to make it up the beach and become not-dead.

RIP to everyone who didn’t make it through that day and to everybody who has since passed away. If there is a wireless connnection to be had then Blackberry or laptop will be used by TheEye to let random co-conspirators from around the world what is happening. Emotion may be too high so a day or two of blogging silence may occur. However if you are in Arnhem and you want to indulge in much wine with TheEye then leave a comment in the traditional place. TheEye doesn’t have the slightest doubt that St Crispin, on whichever compass bearing he may be on that day, will be nodding his head and raising a glass.

Films have shown how the red berets of 6th Airborne Division captured Pegasus Bridge but according to General Miles Dempsey, commander of Britain’s 2nd Army at the time, the story of the exploits of D-Day+1 by the Green Berets of 47 Royal Marine Commando is just as brave.

There were just 420 of them in all, and they had been given the near-impossible task of capturing Port-en-Bessin – a heavily-fortified, strategically vital port from the same crack German unit – 352 Infantry Division – that would cause great loss of life during the American landings later on nearby Omaha Beach.

The problem was that it was the French side of the planned Pipeline Under The Sea (PLUTO) which was so crucial to the invasion so it was a vital target.

Stand on the harbour wall, with your back to the sea, and you’ll understand what a challenge these boys (aged mostly between 18 and 22) faced. Rising up either side there are two huge cliffs which, under Rommel’s Atlantic Wall defence plan, had been riddled with a network of trenches, mortar pits, dugouts and bunkers, guarded by minefields, barbed wire and flame-throwers.

The Royal Marines of 47 RM Commando were extremely fit, highly committed volunteers who had been preparing for 18 months for this operation. But despite their rock-climbing training in St Ives, and their beach landings on the Scottish coast, their CO, Lt Col Phillips, realised that a frontal assault from the sea would be suicide.

Instead, he decided, they would land 12 miles away on Gold Beach, then infiltrate behind enemy lines and sneak up on Port-en-Bessin from the rear. First, though, they had to get ashore in one piece. “The seasickness was appalling,” recalls George Amos. “My m emory is of sitting there, hands green with bile when suddenly there was an almighty bang as our landing craft was hit. You felt it right through. I was carrying a Thompson machine gun and a Bangalore torpedo, but when you’re fully loaded you can’t swim, so you get rid of your equipment. I came ashore with nothing.”

emory is of sitting there, hands green with bile when suddenly there was an almighty bang as our landing craft was hit. You felt it right through. I was carrying a Thompson machine gun and a Bangalore torpedo, but when you’re fully loaded you can’t swim, so you get rid of your equipment. I came ashore with nothing.”

Amos wasn’t the only one. Some men landed without boots or even trousers. The medical officer John “Doc” Forfar (later to win an MC), lost all his surgical instruments; the heavy weapons troop lost their 3-inch mortars; and signals, their wirelesses. Worse still, the unit had already lost a fifth of its strength, killed, wounded or lost. Now, damp, shocked, and pitifully armed, they still marched on Port-en-Bessin.

Follow the troops’ route today and you’ll pass through gorgeously verdant, rolling Normandy countryside, dotted with orchards and lovely old farmhouses. In June 1944 it was much the same, only with scattered dead cows (killed by the allied naval bombardment) and the ever-present possibility that behind each innocuous hedge lurked a Spandau machine gun ambush. As Doc Forfar puts it: “Every bush, every bend in the road, every noise has a potentially ominous significance. You’re alert the whole time.”

About two miles outside Port-en-Bessin, there is a wooded hill with a grassy crown covered with orchids called Mont Cavalier. It was here that the surviving men of 47 RM Commando spent the night of D-Day, the twin peaks of the Eastern and Western features brooding ominously on the horizon. They had supplemented their weapons with German Schmeissers and Spandaus, captured in firefights along the way.

On the morning of June 7, they had got safely through the outer defences and headed into the port when disaster struck. While clambering up the steep slopes of the Western feature, one of their troops was caught out by withering fire from two German Flak ships, which were unexpectedly moored in the harbour. Eleven men were killed, 17 wounded and one – George Amos – captured. Meanwhile, back on Mont Cavalier, the unit’s rear HQ was overrun.

By the evening of June 7, the Commando was in a desperate position: isolated and under constant threat of counterattack from numerically superior enemy forces; low on ammunition, depleted by heavy casualties and exhausted after two days’ fighting with no more than two hours’ sleep. And still those impregnable features loomed.

It was gallant, no-nonsense Captain Cousins who found the solution. On recce patrol he discovered that leading up the side of the Eastern feature was an apparently undefended zigzag path. Under cover of darkness, he led a party of 25 men as far as he could go up the hill unobserved. Then, in true commando style, yelling, screaming and firing from the hip, they charged the enemy bunkers.

At the forefront of the attack was pint-sized Geordie Bren-gunner Arthur Delap. “When the grenades went off in front of us it was terrible,” he recalls. “There were big flashes in front of my eyes. No pain, but my ears were ringing a lot and I was deaf and concussed for a few seconds. Then I started shooting again and after that they put their white hankies up and surrendered.” Beside him, his much-loved troop commander Captain Cousins lay dead, after a selfless act of heroism that many in the Commando believe should have won him the VC.

The path is still visible today, as are many of the old bunkers and zigzagging connecting trenches of this once terrifying fortress.

And on the opposite side of the town, next to 47 RM Commando memorial on top of the Western feature, is the bunker where George Amos was held captive. Rather unnervingly, directly behind where he sat, is a poster advertising Hitler’s infamous Commando Order decreeing that all captured commandos should be summarily executed.

“Because when they captured me I was tending my wounded Sergeant, the Germans thought I might be a ‘sanitator’ – a medic,” Amos recalls. “By that stage I’d worked out that everyone was going to be shot except sanitators, so when they asked me to deal with their woun ded I pretended to know what I was doing. Later they gave me a cup of acorn coffee and I went to sleep. Next thing I knew I was being woken up and the whole German garrison was surrendering.”

ded I pretended to know what I was doing. Later they gave me a cup of acorn coffee and I went to sleep. Next thing I knew I was being woken up and the whole German garrison was surrendering.”

In the months after D-Day, Port-en-Bessin became a vital role in the Allied Normandy breakout as the destination for the Pipeline Under The Ocean (PLUTO) which pumped millions of gallons of fuel under the Channel to France from the English coast. Today, sitting outside one of the fish restaurants that line the cobbled road by the inner port, you’d really never guess that so tranquil a resort could have seen such awful fighting.

Now TheEye is a Round Tabler and has polished the chairs of a few fellow Tables including that one with the Tapestry thingy in France (has a large dull cathedral with stained-glass and unenterprising stonework but the crypt is worth a good look and there is a local watercolour artist with talent you could only dream of). There is also a locally based but internationally famous porn star that TheEye had the pleasure of meeting (NO, and just relax, it was just dinner).

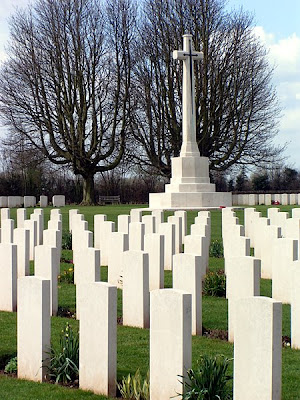

However look at the photograph of one of the places that TheEye visited in Bayeux. If a speck of moistness doesn’t dampen your eye then this blog really isn’t your place.

Recent Comments